They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead: Jazz Explained

They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead is a 2018 Netflix original documentary that tells the story behind Orson Welles’ last movie, The Other Side of The Wind. Directed by Oscar winner Morgan Neville (20 Feet from Stardom, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?) and narrated by Alan Cumming, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead contains testimony from cast and crew from The Other Side of The Wind, as well as testimony from Welles’ friends and family.

While focusing on Welles’s last creative endeavor, this documentary takes a comprehensive approach to the iconic director’s career, providing historical and artistic context, but ultimately focusing on the last fifteen years of his life, much of which was spent working on that last movie, while struggling against insufficient financial backing, and legal and logistical problems. Unfortunately, Welles died in 1985, before he could finish it.

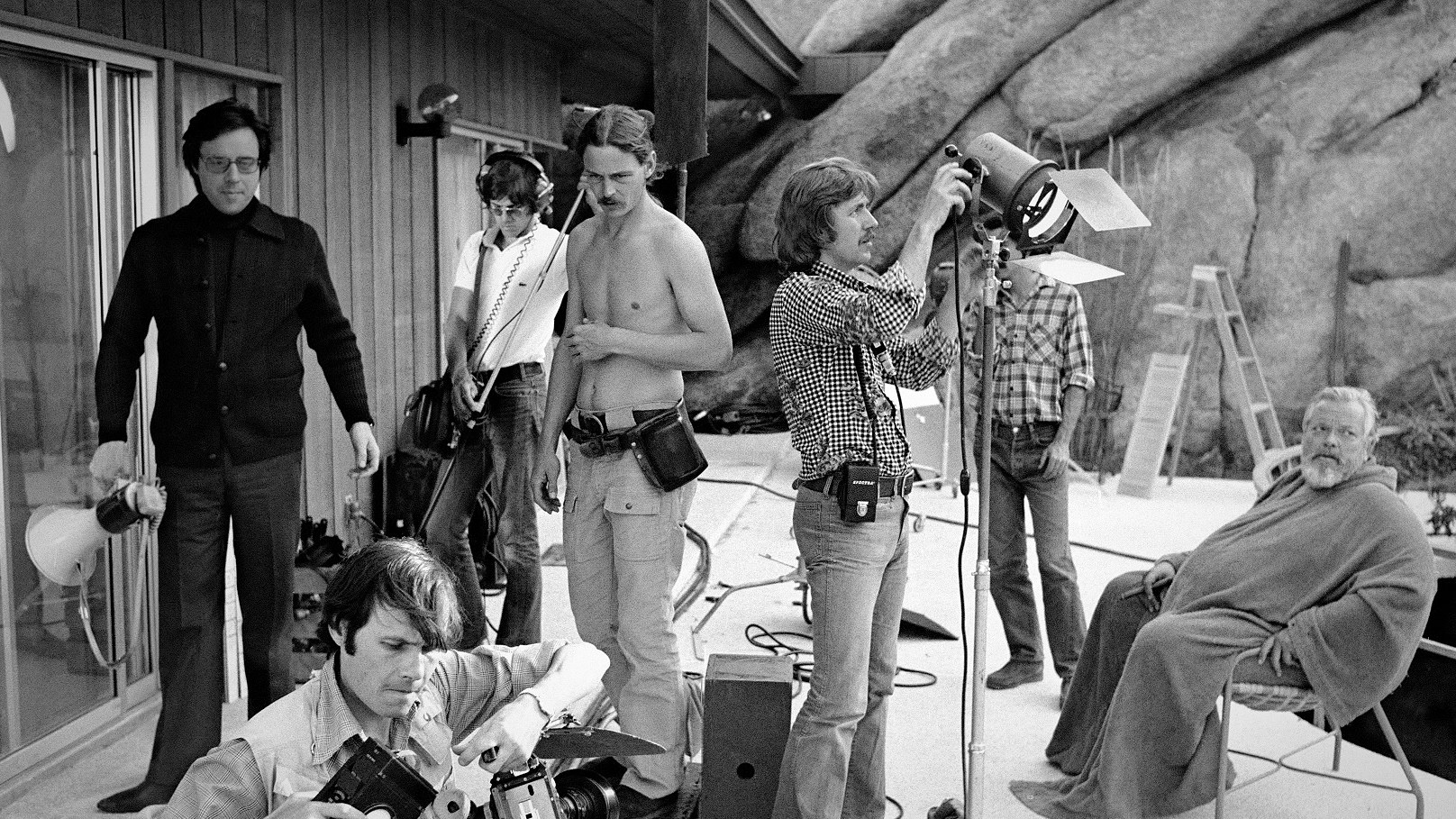

The Other Side of The Wind was finally released last year (also by Netflix). Completed under the supervision of director (and Welles’ close friend) Peter Bogdanovich, and Frank Marshall. Both had worked with Welles originally during the initial shooting in the early seventies: Bogdanovich with an acting role and Marshall as a production assistant.

Oscar winner Bob Murawski (The Hurt Locker), a film editor who joined the project in recent years, did the editing. When Murawski joined the team he found that they had about a hundred hours of footage (shot over a six-year period), about 40 minutes of footage that Welles had edited, and about an hour of rough assemblies of multiple takes thrown together. Leaving Murawski with the task of editing two-thirds of what became the final movie.

Beyond those intense last fifteen years of Welles’ life, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead also shines a light on the journey on which The Other Side of The Wind embarked after Welles’ passing: explaining the legal impediments that for over three decades stood in the way of a posthumous completion of the film, but, more importantly, providing an understanding of the artistic sensibility that anybody picking up that torch would have to be attuned to.

The Other Side of The Wind, even by today’s standards, is not borne of a predictable, hermetic, conventional concept – in fact, it is anything but that – so much so, that there is no way to know what Welles’ final product would have been had he been able to finish it. And so, in order to complete it, Welles’s maverick and outsider way of thinking had to be honored somehow.

As enigmatic and mazelike as Welles’s vision was for his last movie (cast and crew alike were seemingly puzzled as to what he was ultimately trying to achieve), They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead offers a glimpse into Welles’ process and mindset going in, and that’s what makes this documentary so interesting.

Just consider what the premise for Welles’ movie was: a historical document of the day of director Jake Hannaford’s (John Huston) 70th birthday, also the last day of his life. Hannaford is at the set, wrapping up shooting for the day, and a mob of students, young directors, critics, and other media have gathered around, having been invited to a screening of the director’s still unfinished movie. Through assigned transportation and carpool, everybody is headed to Hannaford’s home where the screening is to take place.

So you have a high-profile event made up of a cocktail of 70’s Hollywood personalities (some of them, like Dennis Hopper, playing themselves) on various car rides, and the footage of it is purportedly a blend of all the filming, whether it be in color or black-and-white, done by TV and documentary filmmakers, and anyone “who happened to bring 16 and 8 mm cameras” to Hannaford’s 70th birthday party. While, as the narrative unfolds, substantial chunks of Hannaford’s own unfinished last motion picture (an European style art movie with a radically different cinematic language) are inserted, playing out as screenings.

The rapid-cutting pace of the film, with its intricate plot, clever dialogue, and then drastic change of mood and tone, is almost hallucinatory, but it is done with such exuberance and purpose, that there really is no other word for it other than Jazz. And a commonly overlooked fact about Jazz is that its spontaneity rests on the shoulders of studious homework. But, likewise, so does the ability to appreciate said spontaneity. And so, as a viewer, The Other Side of The Wind is your Jazz, and They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead is your homework.

Four minutes into this documentary, we see footage of Welles surrounded by journalists, in what seems to be an informal press conference about The Other Side of The Wind, at this time still in its embryonic faze. When asked about what would the big basic differences be between this picture and anything else he had ever done, Welles replied: “Everything else I have ever done has been controlled (…) but I would like to take a whole story and make the picture as though it were a documentary. The actors are gonna be improvising.”

And then he went on to mention that this was something that no one had ever done before, and essentially say that the making of the movie was going to be an expedition on which he was “going to go fishing for accidents,” preside over them, and embrace the divine ones. “The greatest things in movies are divine accidents,” he would say.

And just to have an idea of how free and fluid Welles’ approach was, when shooting began, Peter Bogdanovich’s acting role in the movie was that of one of the critics, but four years later those scenes had been scratched from the movie, and Bogdanovich was playing the young apprentice director that idolizes Hannaford: a relationship that eerily mirrored Welles’ and Bogdanovich’s real life dynamic.

These nuances and many others (like the quasi-prophetic parallels between Hannaford and Welles: both dead at the age of seventy, both struggling to finish their last movie, both disdainful of the very Hollywood circus they were unable to stay away from) would escape the casual The Other Side of The Wind viewer, if not forewarned by the proper context provided by They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

For the longest time most educated cinephiles spoke of the history of cinema as a timeline with a before and an after that were separated by Welles’ 1941 seminal work, Citizen Kane. He was only twenty-five when he directed, produced, co-wrote and starred in it. But his work after that failed to bring him the commercial success and recognition he deserved.

They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead points out how Welles, with no ability to finance his movies in America, and feeling betrayed by Hollywood, essentially exiled himself in Europe for the better part of two decades. But in 1970, amidst a changing of the guard in Hollywood, there was a reverence for Wells among the new generation of directors, and Welles himself is plotting a grandiose comeback, intent on cementing his legacy, and encouraged by the fact that Hollywood had somewhat caught up with his adventurous, independent, and uncompromising approach to cinema.

The landscape is, more than ever before, ripe with opportunity for Welles’s eternally outside-of-the-box filmmaking. And so he ventures into making The Other Side of The Wind, and yet, despite this unprecedented favorable climate, Welles still has no qualms about satirizing, not only Hollywood, not only avant-garde European film, but also his own flock of acolytes and disciples.

But the personality and flair with which he does it, the social and psychological commentary, the sarcasm, the almost real-time mirroring of real life, the staying true of it all, the coherent collage of so many scattered aesthetic elements – all that is a remarkable achievement in taming chaos. A mockumentary with another film inside it, The Other Side of The Wind still feels experimental today. And its adequate digestion is nearly impossible without a field manual like They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

Unlike The Other Side of The Wind, They’ll Love me when I’m Dead is a real historical document. An important one that offers insight into a genius at work, by all accounts at the height of his artistic vigor, and defiantly independent at a point in life when most people give in to comfort and sell out. We will never know whether Welles’ vision was faithfully fulfilled, or what the impact would have been had he finished his picture on time. But in 2018, no attentive mind is indifferent to the advent of his last statement finally materializing. And They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead is the perfect way to celebrate it.