What Makes an Indie Game?

There’s a lot of discussion, particularly among those of us who spend our days thinking about games, about what really constitutes an indie game. So when my Geek co-writer Mohseen Lala asked me what makes an indie game, I couldn't just give a short answer.

No publisher

This is the most basic tenet of independent development. If the game has been released by a publisher, it’s probably not indie.

There’s a certain amount of grey area, though. A traditional publisher’s role is to get the game into boxes on a shelf and to market the game effectively. The publisher usually has connections with distributors, PR reps, press and so forth; and the publisher usually has the final say on where and how the game will be marketed.

Developers of Playboy:The Mansion, for example, had to take into account what massive retailer Wal-Mart considered inappropriate as they developed content. Playboy needed the sales from physical copies on the shelves at Wal-Mart to be profitable. This model has shifted quite a bit, and for many games, visibility on the App Store or Google Play is much more relevant than physical copies. Many games now are developed for direct distribution platforms like Steam, the app store, or even Facebook, and have no need of a traditional publisher. Facebook giant Zynga has no publisher… but they're far from indie.

There are also a couple of indie publishers, like Wadjet Eye Games, that work with indie devs to market and distribute their games. But for the most part, if the game’s got a publisher, you can cross it off your indie list.

A Small Studio

Indie games are typically made by an individual or a very small team. If the game has six animators, it’s probably not indie. If the animators is also doing six other roles? Probably indie.

Pushing Limits

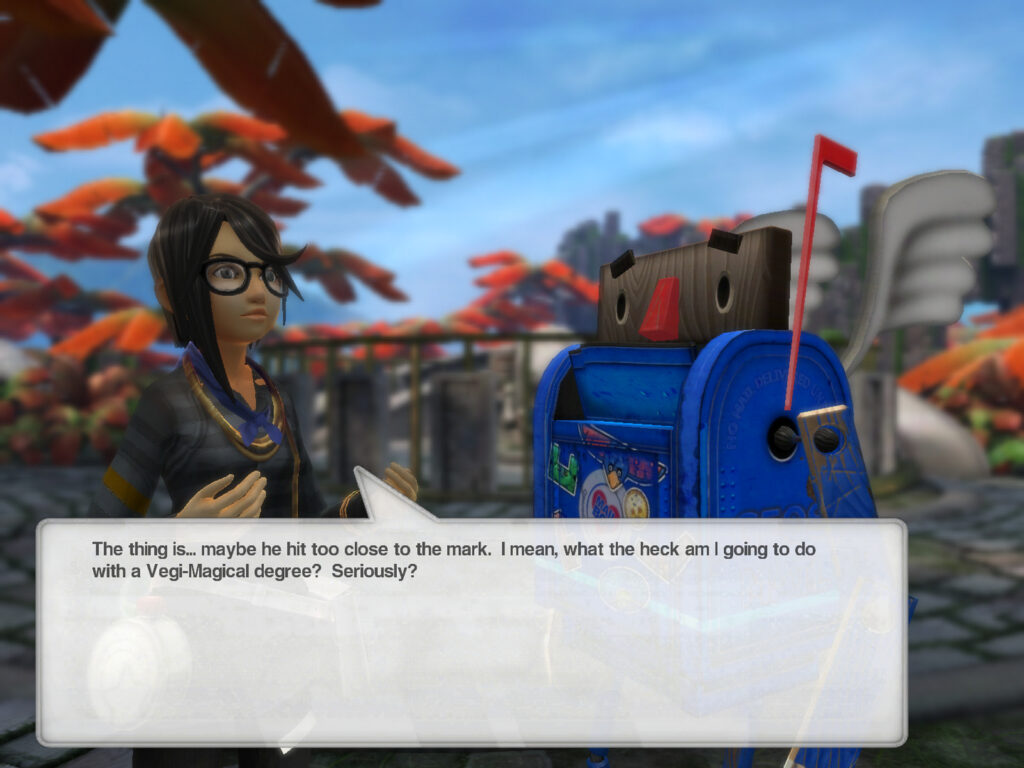

I love indie games because a passion project has the potential to be much more exciting and engaging than a project from a mainstream studio. Sorry, TheSims, Civ and other innovative and beloved AAA games! But indie devs have the ability to turn away from proven mechanics, and proven themes to really try new things; and see what games as a medium can offer us.

A couple years ago, I got to check out Robin Arnott’s experimental indie Deep Sea. In this game, players block out all sound and light by wearing a modified gas mask, and a set of headphones. Inside, they can hear Arnott’s undersea audio and a crackling help request, followed by the terrifying sounds of encroaching enemies. Players use a joystick to move and to shoot at the undersea monsters, attempting to detect undefined hostiles. The sound of shooting and even the player’s breathing attracts the monsters. It is an intense experience, powered by amazing audio, but I can’t see a major studio mass-producing that one.

Depression Quest, discussed in this recent piece on successful serious games, is an artistic interactive statement on depression, and an interesting application for text-based games. There’s no monetization hook that would make it profitable for a mainstream studio — there’s no self-medicating with in-app purchases of beer or trashy TV.

Good indie games take great advantage of this freedom from traditional forms and profit models.

Browsing the App store shows a certain number of studios who reskin popular iOs titles and release them under similar names. These can look like indies — small studio! no publisher! — but a closer glance reveals a highly derivative product like a physics puzzler Angrier Birdies or a match-three Bedazzled. While it’s hard to come down too harshly on the existence of more games or more for game developers, I'm not interested in the three-hundredth low-budget Temple Run knockoff.

Graphically Unimpressive? No!

That is a vicious myth! A lot of retro 8-bit games are indies, but there’s no reason an indie has to be graphically unimpressive.

Lili. Osmos. Dear Esther. Machinarium. Puzzle Bots. Should I go on?

What would you add to your definition of indie?