What Makes A Survival Horror Game Decent?

As I mentioned in my review of Outlast, I’ve heard many people claim it to be a better horror game than A Machine For Pigs. In my experience, this wasn’t so at all. I thoroughly enjoyed both games – albeit for different reasons – and found that both were equally worthy of being part of the horror genre. At a certain point, I then got to thinking…what do the two games have in common?

More than that, what actually makes a horror game decent? What separates acclaimed titles like Amnesia from abortions like Geist? What’s the difference between a game that inspires pants-wetting terror, and one that simply envelopes the player in crushing boredom?

Let’s talk about that.

The Monster

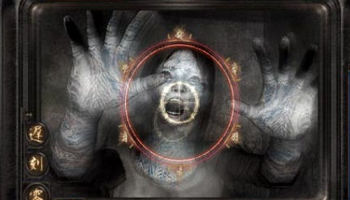

Every good horror game features, at its core, something which pursues the player/protagonist, usually (but not always) a monster of some kind (or several). This creature or force is, if not the primary antagonist, almost always a driving element of the plot; the player’s efforts to avoid an encounter with the monster – which will almost always end in their death – tend to make up the core gameplay in pretty much every horror game out there.

The monster needs to be something the player fears. It needs to instill in them a fight-or-flight response. Truth be told, this is where most horror games tend to fail. The monster, for whatever reason, isn’t disturbing enough. As a result of this, everything else kind of just falls flat.

But what exactly makes a creature disturbing? When is a monster considered grotesque enough to instill fear?

Well, first and foremost, it represents a real threat to the player. Getting caught by the monster – or even seeing it – generally means you’re just a few seconds away from reloading. To drive home this terrifying invulnerability, the vast majority of horror games now don’t tend to give the player any sort of offensive ability; their choices ultimately boil down to run, hide, or die. In the event that a game does give a player a means of defending themselves, it’s usually horribly ineffective or incredibly difficult to wield.

There’s a good reason for that. Playing someone who’s a capable soldier– someone who can easily gun down hordes of monstrosities – simply doesn’t have the same impact as playing someone who is, for all intents and purposes an ordinary, helpless schmuck; same as how hiding from something like a frightened child doesn’t have the same effect as shooting it in the face.

Subtlety is also incredibly important in a monster. There’s an old adage in horror: less is more. The less you see of a frightful creature, the more you tend to fear it. A lot of lower-grade survival horror games tend to overuse jump scares, or toss out monsters that are highly visible and easy to see. Sure, they’re gruesome to look at…but after you’ve stared at ‘em for a while, they’re not really all that frightening.

There also needs to be something about the monster that’s designed to rattle the player. Maybe it’s the unnatural sound it makes. Maybe its appearance is particularly grotesque, or its behavior and movements so abnormal that it can’t possibly be of this world. Whatever the case, the monster actually needs to be frightening, it needs to stab itself straight into the center of the brain that deals with a players’ deepest, most primal fears.

Amnesia: The Dark Descent is a good example of these concepts in practice. Simply looking at the monsters drains your sanity meter (causing the screen to blur, among other things), and getting caught by one spells death. The brief glimpses you see of them are enough to scare you – your mind fills in the blanks. At the same time, the game does tend to overuse them a bit towards the end, and they definitely become a bit less frightening as a result.

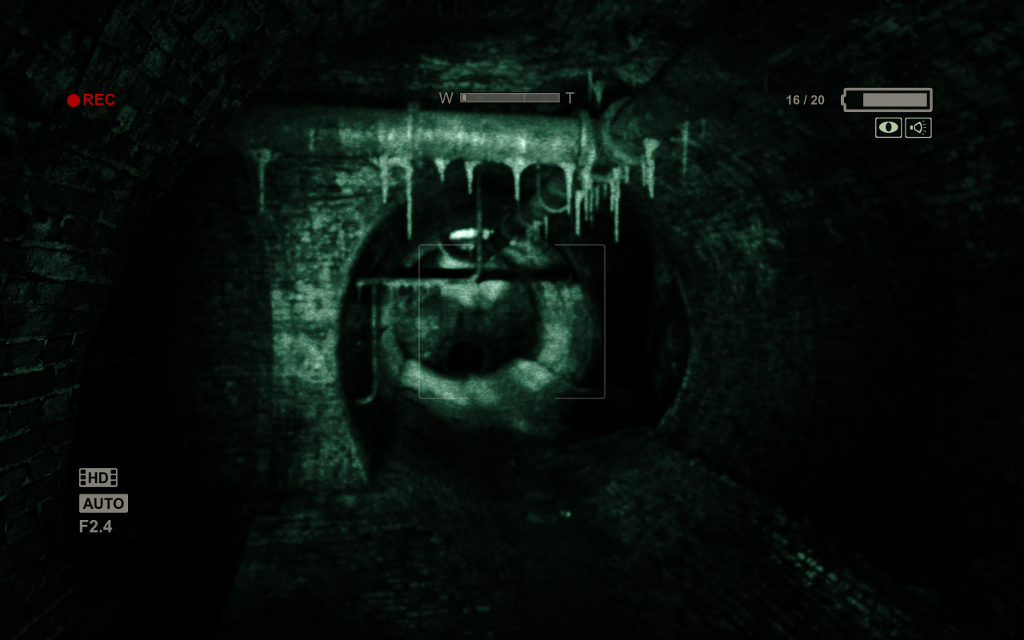

Surviving

Your mileage may vary on this one, but most horror games have some sort of mechanic that forces the player to carefully manage their time. Sometimes this is a representation of the player’s health or mental well-being. Sometimes it’s supplies such as batteries or lantern oil. The presence of such a mechanic more or less ensures that the player remains frantic, desperate, and anxious; even when they aren’t being actively hunted.

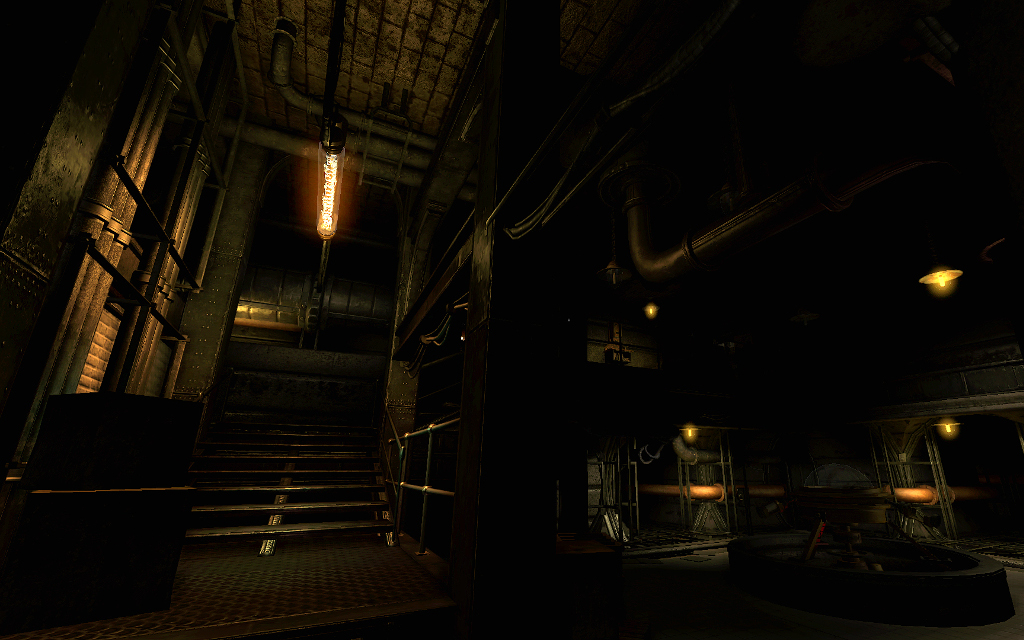

The Environment

This is something that A Machine for Pigs did an incredible job of pulling off. The monster in a horror game isn’t always the most terrifying thing there. If a developer can instill a sense of dread simply through the player’s surroundings – by using unpleasant images, sounds, subtle cues, darkness, or conditioning (more on that in a moment) – they’ve already got half their job done for them. I’ll give an example here. If you haven’t played A Machine For Pigs, you might want to skip over this next part.

At one point during the first half hour or so of the games, Mandus is alone in his home. Paintings of pure chaos and mania adorn the walls of his estate, and occasionally – seemingly at random – the player hears screams of terror, agony, and death. At one point, while the player is wandering through one of the many secret passages that honeycomb the house, they see a large bedroom with…something on the bed. A pig, perhaps?

It’s not really clear. Anyway, the player pulls a switch, opens a door, and returns to that same room later on. At that point, they make a rather unnerving discovery.

The bed is empty, and a trail of blood leads straight to the door where the player is standing.

By doing this, the game sets the player immediately on edge, even though they don’t actually start encountering the game’s monsters until at least a full hour later. There’s a palpable build-up of anxiety; an air of immense tension that makes every sound and shadow feel like a new threat. At many points, the environment – discomforting enough simply by its appearance, even more so by the noises that surround the player – is the most frightening aspect of the game.

Game Mechanics

This one is pretty simple, so I’m not going to spend too much time on it. Unique mechanics and concepts are always welcome in a horror game; the most innovative titles are often the best. At the same time, a game where the character controls like an inflexible hunk of metal attached to a string isn’t going to work; players are going to be so frustrated with the control scheme that they won’t be too scared. Whatever controls a developer implements in their title, they need to be polished.

The Narrative

The player knows they’re being pursued…but why? What’s after them? What brought them to this place, and what’s stopping them from simply getting up and walking away. In Outlast, Miles is trying to leave the asylum – without success, I might add. In The Dark Descent, there’s no point to fleeing – the creature that’s after Daniel will pursue him no matter what. In A Machine For Pigs, Mandus desperately wants to find his kids. In Silent Hill, well…the town won’t really let anyone out. The list goes on and on, and all the games have one thing in common.

For one reason or another, the characters aren’t going anywhere, as much as they may want to turn tail and run.

A good narrative – one that offers at least a passing explanation of why the character’s in their current situation (and why they don’t just walk away) may not be vital to a good horror game, but it’s nevertheless extremely important. Bonus points if the narrative is disturbing.

Mind Games

Now, here’s the most important element; the thing that separates the great horror games from those that are merely decent. They toy with the player. They take the player’s perceptions, and turn them on their head. They condition the player with a series of sounds, images, or triggers that represent a monster or a threat…then gleefully start using those triggers at random, even when no threat exists.

Basically, they make the player question their own judgment. They combine the fear they inspire with a deep, abiding uncertainty. In doing this, a player who might simply be unnerved becomes afraid. A player who might be afraid becomes panicked. A player who might otherwise be panicked stops the game, stands up, and goes outside to take a break.

Once again, I’m going to use A Machine For Pigs as an example. The game’s monsters cause Mandus’s lantern to flicker whenever they approach. If your lantern starts flashing, they’re most definitely somewhere in the area. Except that they aren’t. Later in the game, the lantern starts flickering at random times. The player, in a panic, starts to look for a place to hide, until finally realizing there’s really nowhere for them to go.

The best horror games don’t simply scare you. They get inside your head, and trash whatever they can get their claws on.